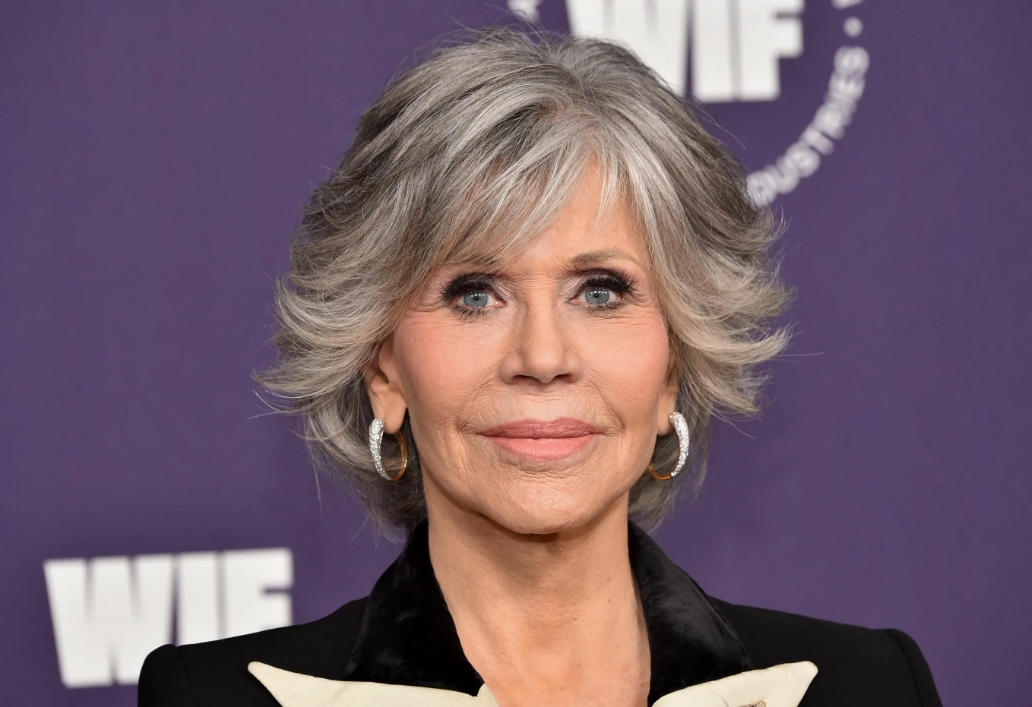

At the gates of Sydney Airport this January, the usual hum of transit fell away as a silhouette of undeniable stature emerged. Jane Fonda, draped in a chic navy coat and oversized shades, moved through the terminal with an unflappable poise. While she occasionally utilized a wheelchair—a logical “throne” of efficiency for a global traveler at 87—she soon stood to walk, undeterred and kinetic, signaling that she wasn’t just arriving in Australia; she was occupying it. She is here to discuss the “gift” of aging, a reclamation of life that she frames not as a slowing down, but as a shedding of weight.

There is a profound paradox in the way Jane occupies her late eighties. She has famously claimed to feel younger now than she did at twenty, a statement that at first sounds like a Hollywood platitude but reveals a visceral truth upon closer inspection. In her youth, she was the daughter of Henry Fonda and a “silver screen siren” tasked with embodying a specific, often suffocating, ideal.

Today, she has traded that psychic burden for the “lightness” of purpose. The kinetic energy once spent on leg-warmers and the 1980s workout revolution has evolved into a selective fire; she now engages in a modified daily routine—a celebration of the machine—while focusing her fiercest curiosity on environmental activism.

This preservation of power extends to her craft. Fonda is a 60-year archive of excellence who famously refuses “sad” roles written for older women. It isn’t diva behavior; it’s a refusal to let a subpar script diminish her scars or her story. She is an actress who won’t settle for being a peripheral accessory when she is clearly the main event.

As she takes the stage at the ICC Sydney Theatre, Jane Fonda is proving that the Third Act is where the true narrative tension lies. She isn’t just aging with grace; she is aging with an unapologetic, rebel-activist spirit, showing the rest of us that the end of the script is actually where the real life begins.