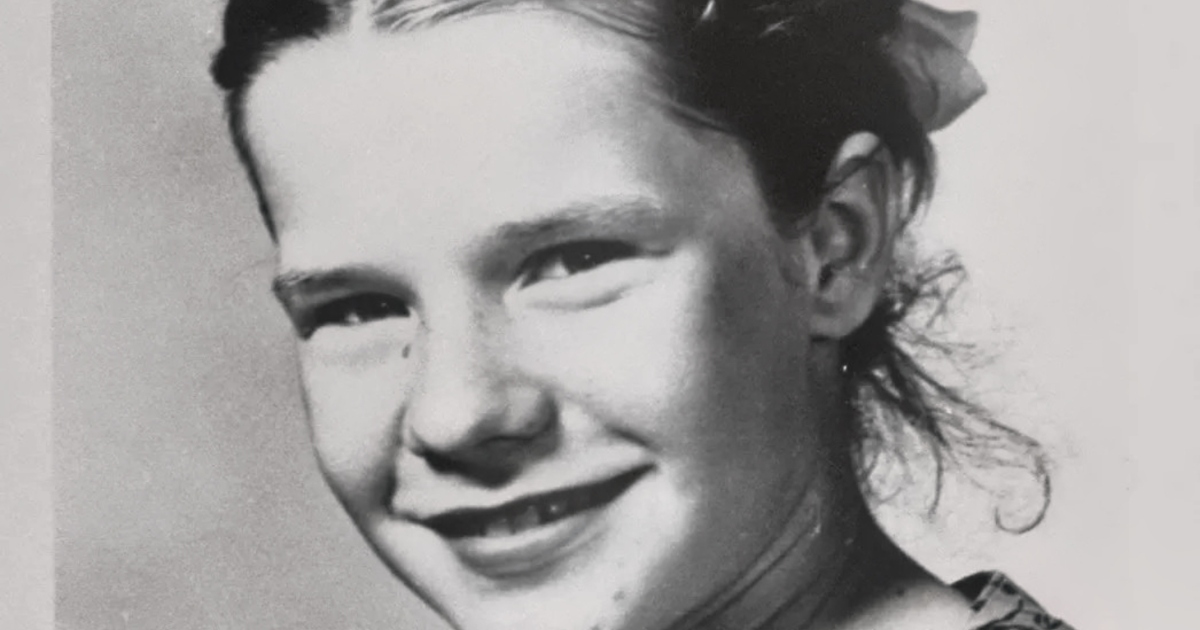

Imagine a young girl in Port Arthur, Texas, whose face was a map of “biological cruelty.” Suffering from severe, painful acne and a style that refused to conform, Janis Joplin was a target long before she was a titan. The “social stressors” of her youth hit a jagged peak at the University of Texas, where a fraternity’s cruel “ugliest man on campus” prank left a permanent scar on her psychological landscape. But Janis did something the world didn’t expect: she took that trauma and turned it into an electric, raw frequency.

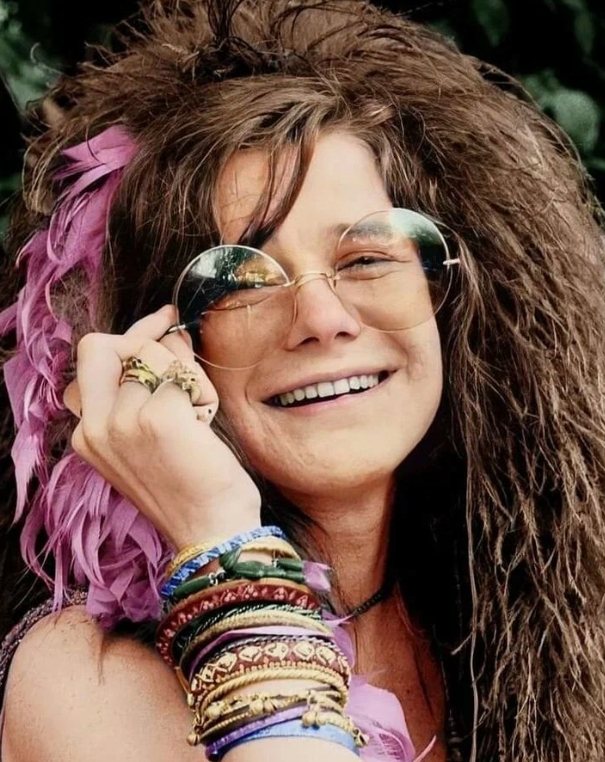

She didn’t just sing; she weaponized her entire respiratory system to produce a raspy, “kinetic energy” that vibrated through the marrow of her listeners. By the time she stepped onto the stage at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, she delivered a “neurological shock” to the industry. Those perceived defects were gone, replaced by a source of immense cultural power. She was no longer the girl being mocked; she was the high priestess of rock and soul.

Yet, behind the beads and feathers, her “internal homeostasis” was fragile. The scars of her youth created a desperate need for external validation. Janis often spoke of the “dopamine crash” that followed her performances—the crushing silence that felt like a physical weight once the crowd’s roar faded.

She sought “chemical escapism” to manage the lingering pain, a tragic attempt to regulate a heart that had been ostracized for far too long.

Janis became the architect of “aesthetic autonomy,” rejecting the polished feminine standards of the 1960s. She proved that “unconventional features” are synonymous with magnetic beauty when fueled by talent. She turned her history of exclusion into a narrative of radical inclusion. Today, the cruel jokes of her past are mere footnotes to a legacy of foundational grit. Janis Joplin taught us that the very things meant to break us can become the fuel for our greatest triumphs.